Acas Capability Dismissal

James Gutteridge reports on an EAT decision which looked at whether the Acas Code applies to dismissals for ‘some other substantial reason’, where the working relationship had broken down between the parties.

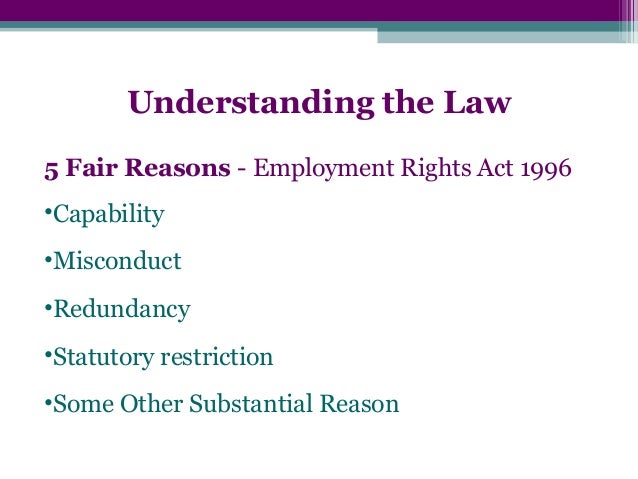

EMPLOYMENT LAW TOPIC: DISMISSALS LECTURE 4 UNFAIR DISMISSAL Key topics. Rules for Conduct dismissals & ACAS Code of Practice. Basic award – Week’s pay. Maximum amounts – week’s pay & compensatory award. Compensatory award – heads of loss, including loss of statutory rights. Overlapping remedies. Application of topics from lecture 3. Critical discussion of need to. Reasons for fair dismissal. By law, there are 5 potential reasons for dismissing someone fairly. These are: conduct – when the employee has done something that's inappropriate or not acceptable; capability – when the employee is not able to do the job or does not have the right qualifications; redundancy – when the job is no longer needed.

The background

Capability or performance is about an employee's ability to do the job. Some employers might have a separate procedure for dealing with capability or performance issues that should be based on: support; training; encouragement to improve; Whether the employer deals with the issue under a capability or disciplinary procedure, they must do so fairly. If a capability issue is linked to someone’s health. To make sure the dismissal is fair when misconduct is not ‘serious’ or ‘gross’: Arrange a meeting with the employee, telling them. Acas and SOSR dismissals. James Gutteridge reports on an EAT decision which looked at whether the Acas Code applies to dismissals for ‘some other substantial reason’, where the working relationship had broken down between the parties.

Since the entirely unlamented demise of the Statutory Disciplinary and Grievance Procedures back in 2009, employers have been required to follow the Acas Code of Practice (‘the Code’) when dismissing for misconduct or capability. The Code explicitly states that it does not apply to redundancy dismissals or to the expiry of fixed term contracts; but it is silent as to whether it applies to dismissals for ‘some other substantial reason’ (SOSR), under section 98(2) of the Employment Rights Act 1996. This is the residual ‘catch-all’ potentially fair reason for dismissal, and is often used in circumstances where an employer wants to dismiss because working relationships have broken down.

When an Employment Tribunal makes a finding of unfair dismissal and then turns to consider the Claimant’s compensation, it must decide

- whether the Code applied; and, if so

- whether to exercise its discretion to apply an uplift of up to 25% to the Claimant’s compensation because of any failure by the employer to follow the Code.

In a 2010 case called Cummings v Siemens Communications Limited an employment tribunal took the view that the Code did apply to SOSR dismissals – but, as a first instance decision, it was not binding.

The question of whether a dismissal because working relationships had broken down was a SOSR or misconduct matter was considered in 2011 by the EAT in Ezsias v North Glamorgan NHS Trust . In that case, the EAT said that the dismissal was a SOSR – please click here for a summary.

This month, in Lund v St Edmunds School, Canterbury , a decision of the Employment Appeal Tribunal has, on one hand, provided a little more light on the question of whether SOSR dismissals fall under the Code but, on the other hand, may have muddied the waters further.

The facts

The Claimant, Mr Lund, worked for St Edmunds School (‘the School’) as a Graphic Design teacher. A conflict between Mr Lund and the school arose because of Mr Lund’s apparent frustration with the computer equipment with which he had been provided. Mr Lund dismantled the system, and also refused to allow a consultant, who had been engaged to report on his teaching, to observe his class. Mr Lund was then away from work, initially due to stress and then because he was suspended by the School. The School then asked Mr Lund to attend a meeting, at which he was handed a letter notifying him of his summary dismissal. The letter referred to the School’s concerns about what they described as Mr Lund’s “erratic and sometimes irresponsible” behaviour, and his attitude towards colleagues which they characterised as “difficult and unhelpful”. The School concluded the letter by informing Mr Lund that his employment was terminated with immediate effect because “the trust and confidence essential to an employment relationship has broken down.”

Mr Lund succeeded in claims of unfair dismissal and wrongful dismissal. The tribunal found that the dismissal was both procedurally and substantively unfair. The award of compensation was reduced because the tribunal felt that Mr Lund had contributed to his own dismissal because of his intransigent attitude, with contributory fault being assessed at 65%. No uplift was made, pursuant to the Acas Code because

- Mr Lund had contributed to his own dismissal; and

- the Acas Code is silent about whether it applies to SOSR dismissals.

Mr Lund appealed against the tribunal’s decision on the award of compensation.

The decision

The Employment Appeal Tribunal (EAT) said that Mr Lund’s behaviour was not relevant to whether the Acas Code applied to his dismissal and, consequently, whether the uplift should not be applied to his compensation. The EAT noted that the uplift is intended to penalise employers for failing to comply with the Code, and that Mr Lund had done nothing to contribute to the School’s failure in that regard. Moreover, his compensation had already been reduced by 65% because of his behaviour, so to deny him the uplift as well would amount to “impermissible double accounting”.

The EAT then went on to look at whether the Code applied to Mr Lund’s SOSR dismissal. The EAT said that the Code did apply.

Importantly, the EAT said (at paragraph 12 of its decision) that it is not the ultimate outcome of the process which determines whether the Code applies; it is the initiation of the process which matters. The Code applies where disciplinary proceedings are, or ought to be, invoked against an employee.

In Mr Lund’s case, the process by which he was dismissed was covered by the Code because the tribunal had found that the School had a disciplinary process in mind when it instigated the process that eventually lead to Mr Lund’s dismissal. Ultimately, Mr Lund was dismissed for ‘some other substantial reason’, which was a non-disciplinary reason – but the EAT said that this is to “look through the wrong end of the telescope”. On the tribunal’s understanding of the factual circumstances, the Code applied to the process which resulted in Mr Lund’s dismissal because the disciplinary procedure was the mechanism which the School had used to decide whether Mr Lund should continue in the School’s employment.

So, once Mr Lund’s conduct had been called into question and, crucially, that it was thought this his conduct might lead to his dismissal, the School should have invoked the disciplinary procedure, notwithstanding that the School ultimately decided to dismiss for a non-disciplinary reason.

This is why Mr Lund’s case was decided differently from the Ezsias decision outlined above, despite their similar facts. In Ezsias, it was found that the Trust never contemplated dismissing Mr Ezsias because of his conduct. The Trust dismissed because of the breakdown in Mr Ezsias’ working relationships with his colleagues; conduct was the cause of the breakdown in working relationships, but not the reason for the dismissal.

What does this mean for me?

This leaves us with a somewhat complicated, and potentially confusing, result. The EAT has not gone as far as saying, categorically, that all SOSR dismissals are covered by the Acas Code. The decision appears to say that the Code is invoked as soon as misconduct is considered by the employer, regardless of whether misconduct is ultimately the reason for the dismissal. Presumably, the same reasoning would apply to capability dismissals, as these are also covered by the Code.

A curious aspect of this case is that the EAT’s decision means that the Code applies not only where the employer has invoked disciplinary proceedings, but also when they ‘ought’ to have done so. This will involve employment tribunals undertaking a speculative exercise over what an employer ought to have done, as well as what they did do.

As Alice in Wonderland famously said: “curiouser, and curiouser…”

For employers, the safest way of dealing with this conundrum is to ensure that the Code is followed if there is any doubt about its applicability, and to ensure that the Code is followed as soon as any question of misconduct arises. This will usually be relatively easy to accomplish, as the basic procedure set out in the Code is very simple, and most large employers will go beyond the basic requirements of the Code in any event.

In a nutshell

A capability process allows an employer to help improve an employee's poor performance or deal with possible incapability due to ill health. It is to encourage improvement in performance and ascertain the seriousness of illness so that the employee understands and meets the required standards of work, or to ensure that you support the employee should illness/long-term sickness be the issue: for example, exploring all aspects with a view to, where the employee is disabled, making reasonable adjustments such as investing in suitable equipment.

Some employers will use the disciplinary procedure to deal with such matters – for more information please refer to the section on discipline.

A written capability policy and procedure should be in place to ensure that employees are aware of and understand the required standards of work and attendance in the workplace. This should be in the staff handbook where examples may be detailed.

In the cases of unsatisfactory performance or the employee taking sick days here and there, initially, these may be dealt with informally. If, however, they continue or are of a more serious nature, you may have to move to a formal process which means instigating the capability procedure. For example, the employee may have missed a couple of deadlines and it is felt that this should be dealt with informally with it being made clear, once the reasons as to why have been explored, that this should not happen: should this continue and it affects the work, then you may decide to instigate the formal capability procedure.

It is usual for the employee's manager to deal with capability issues, however, if this is not possible, another manager may deal with the matter or external support from Acas or a third party such as an HR consultant may be another option. There must be no bias or discrimination within the process and written records and documentation should be kept throughout. This provides a record of the investigation, the discussion, the outcomes and the expected change in performance or the arrangements regarding illness/sickness. The outcome may be dismissal which the employee can appeal and potentially bring a tribunal claim in which case all records will be required.

The capability process must be fair and transparent and, where the employer does not have a written policy and procedure, it is advisable to follow the Acas Code of Practice for Discipline and Grievance and adapt it for capability. This Code is recognised by the tribunals as the best practice way of handling a disciplinary situation and can be used alongside the Acas guide 'Discipline and grievances at work'. However, the employer should note that the actions at the first stage of a capability process are different to those of the disciplinary process. In this case, with job performance issues, the employee should receive an improvement notice. This notice explains what needs to be done in order for the employee to bring his/her work up to the required standard(s) within an acceptable timeframe. This may include suitable support from the employer such as coaching or training.

Why this matters

When dealing with issues around poor performance or incapability due to ill health as an employer there are a number of related issues which could lead to employment tribunal claims (for example disability discrimination) or which could turn into other procedures relating to discipline or dismissal. As a result it’s vital that you have a clear process and understanding of how to effective manage matters relating to capability.

Key steps to manage this issue

1. Establish the facts by investigating and meeting with the employee

Poor performance

For poor performance, you should investigate and establish whether there is a lack of application by the employee. Where that is the case, then you may consider using the disciplinary process: for example, the employee may just be not bothering to do the work as they hate the job. It may be that it is the employee's lack of ability: for example, they may require some further training to bring them up to the required standard.

Where you considers it is due to a lack of ability, the employee should be informed, in writing, of:

- exactly how their work is not meeting the required standard

- the expected standard(s)

- the timescale of expected improvement and that the employer will assess the employer at that time

- support, coaching and/or training that will be given to the employee.

Providing that you have given the employee the above information and that it is reasonable, and with sufficient detail so that they can make those improvements, then you can consider dismissal at the end of the improvement notice period should the required standard(s) not be met.

Next, you should invite the employee to a capability hearing informing them:

- of the shortfalls in the standard(s) of their work

- that the final decision could result in dismissal

- of any evidence that support your view

- of their right to be accompanied by a work colleague or trade union representative.

Where the employee has not reached the required standard:

- consider a further period for improvement in the employee's performance

- consider whether there is another vacancy that suit the employee's abilities

- consider dismissal.

Then, inform the employee in writing including their right to appeal (including how they appeal, to whom, and in what timeframe).

Ill health

Where an employee is off sick for a prolonged period and it is deemed unlikely that they will be well enough to return to work within a reasonable timeframe, you can fairly dismiss.

The nature of the role and the difficulties you have encountered in covering the absence should be taken into account when determining what may constitute a reasonable time.

It is of note that even where the role has been covered easily and where cost has been negligible, there is no obligation on you to keep the role open indefinitely.

Before you can justify dismissal on the grounds of sickness, you must:

- Investigate the circumstances to ascertain how long it is likely to be until the employee returns.

- Invite the employee to a meeting to discuss all of the information you have in order to put forward their point of view and if they think their role should remain open for a longer period of time.

The investigation should include speaking with the employee and investigating the medical issues.

You can ask the employee to authorise an approach for a medical opinion although the employee can refuse. You should be aware that any approach falls under the General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR) and the Access to Medical Reports Act. You may also ask the employee to have a medical examination by a doctor of the company's own choice: there may be a clause within the employment contract detailing this. You can refer to section on managing absence for more information on this.

When writing to the doctor, you should ask him/her whether he/she considers the employee to be disabled and what reasonable adjustments would allow the employee to return. Where it is deemed that the employee is disabled, you should discuss the return with the employee with the consideration to any reasonable adjustments. For example, this may include the use of different equipment specific to their needs that allows the employee to carry out the role.

Should the employee refuse to give their consent to a medical assessment, you may have to make a decision made on all the available information.

Next, invite the employee to a capability meeting and let them know in advance:

- that the decision could result in dismissal

- the medical evidence available

- of their right to be accompanied.

Where the conclusion may be that the employee is unlikely to be well enough to return to their role within a reasonable timeframe, you should give consideration to:

- any other vacancies that are available that the employee could fill either immediately or in the future

- any reasonable adjustment(s) that could be put in place to allow the employee's return (this is for the employee who is disabled).

Inform the employee of the right to appeal.

The meeting

Attendees will vary depending on the capacity of the company. However, ideally the following should attend:

- the manager running the investigation and/or meeting

- an HR representative

- a note-taker

- the employee

- the companion.

If you do not have capacity for all of these people to attend, it may only be the manager running the meeting and the employee. In this case, you may, with the employee's permission, record the meeting: the employee should be provided with a copy of the recording and a transcript

Where the employee is being accompanied, the employee and companion both should make every effort to attend. Where it is not possible for the companion to attend, the employee should inform the employer and the latter should postpone the original date but must ensure that the alternative date is reasonable and not more than five working days after the original date. Where the employee or companion persist in not attending, you may make a decision based on the available evidence.

The companion, on behalf of the employee, can address the meeting, sum-up the employee's case, respond on his/her behalf, and confer with the employee. No other person may accompany the employee other than a work colleague or a trade union representative or an official employed by a trade union: should the employee request a family member or friend accompany them, you can refuse.

At the meeting:

Acas Capability Dismissal

- explain the background and issues

- explain how the meeting will run

- acknowledge whether the employee is accompanied or not; where it is the former, ensure the companion understands their role

- go through the investigation information

- let the employee set-out their case, present any further evidence, and ask questions as well as answering your questions.

2. Adjourn the meeting and decide on appropriate action

When all areas have been discussed, the chair may adjourn the meeting providing time to:

- make a decision, or

- determine whether there should be further investigation, or

- tell the employee that further consideration needs to be given to all the evidence and that you will be writing to the employee in the next five working days. This timeframe is dependent on your policy and procedure.

Next, you should decide on the appropriate action and inform the employee in writing. Consideration must be made of:

- all of the evidence

- the seriousness of the poor performance or the ill health or issues around long-term sickness due to injury. For example, if a person who has a physical job is in an motor accident and sustains injuries that means he/she is incapacitated for a significant period of time (maybe 10 months), how this impacts on the company (see dismissal below).

You must be able to justify the decision. The capability decision(s) may include:

- a longer period of time for improvement

- further medical investigation

- dismissal.

The decision to dismiss may only be taken by the manager who has that authority. This should be clear within the capability policy and procedure.

3. Write to the employee including their right to appeal

The employee must be informed of:

- the outcome: where it is dismissal, the reasons for the dismissal must be outlined

- the date the employment ceases

- the notice period.

An employee who is dismissed whilst off sick is usually entitled to pay for the full statutory notice period. They do not have to work this period and the employer should stipulate this to the employee. Pay is paid for the statutory notice period, that being:

- 1 week's notice if employed between 1 month and 2 years

- 1 week's notice for each year if employed between 2 and 12 years

- 12 weeks' notice if employed for 12 years or more.

Where the contractual notice period for dismissal is longer than the statutory notice period (1 week for each full year of employment), the employee should be paid the statutory amount for the statutory notice period (for example statutory sick pay) and, thereafter, full pay for the remaining contractual notice period.

Where the employee has been given payment in lieu of notice he/she would be paid full pay for the whole notice period.

Information about the right to appeal should include:

- how to appeal

- who to appeal to – usually the manager who has dealt with the process. He/she will pass the appeal request to another manager or external provider dealing with the appeal

- how many days in which they have to appeal from the date of the findings letter

- the reasons for the employee's appeal.

4. The appeal

Where the employee appeals, the appeal hearing should be heard without undue delay.

The appeal hearing manager should write to the employee confirming:

- date, time and place of the hearing

- who will be in attendance

- the statutory right to be accompanied

- the decision made is final and there is no other formal internal recourse.

The role of the companion remains the same as for the capability hearing.

Following the appeal hearing, you should write to the employee with the final decision. This is usually done within 10 working days of the hearing.

5. Where the employee's sickness is caused by the employer

Where the employer has caused the sickness absence, for example an industrial accident, this does not inhibit you from deciding on a fair dismissal. All steps must be carried out as outlined above. The employee, of course, may claim damages for injury and loss of employment if they are dismissed.

6. Where short-term illness is a frequent occurrence

The capability procedure may be used and the principles outlined above, followed. The employee should be informed:

- that the level of sickness is considered unacceptable in the long-term

- if their sickness record exceeds the acceptable levels

- of an improvement period

- where improvement is not forthcoming, the possibility of dismissal

- of a capability meeting to discuss their absence.

Tools and resources

Use the checklist of common capability issues for ideas on how to approach capability issues.

Further information

Legal disclaimer

The materials on this site are for guidance only and do not constitute legal or other professional advice. You should consult your professional adviser for legal or other advice.

The CIPD is not liable for any damages arising in contract, tort or otherwise from the use of or inability to use this site or any material contained in it, or from any action or decision taken as a result of using the site.

This site offers links to other sites thereby enabling you to leave this site and go directly to the linked site. The CIPD is not responsible for the content of any linked site or any link in a linked site and the inclusion of a link does not imply that the CIPD endorses or has approved the linked site.

People strategy

Planning and developing your ‘bigger picture’ strategy

Explore the guidanceGetting support

Additional resources to assist you on your journey

Find out morePeople Skills Blog

Access blogs on an range of people management topics